Normal Buy No. 3, geared up on June 19, 1865, by Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger in Galveston, Texas, introduced the end of legalized slavery in the state. This was some two years soon after the Emancipation Proclamation and two months soon after Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. In “On Juneteenth,” historian Annette Gordon-Reed describes the function as a source of excellent satisfaction statewide and considers the go to make it a countrywide getaway a tribute to the exceptionalism of Texas in every single regard. (However in the wake of past year’s social justice protests, it has also come to be an option for commercialization.)

In addition to offering a context for an function that has come to be a touchstone for Black celebration, “On Juneteenth” is also a Black Texan’s powerful examination of historical past as a result of the lens of personalized memoir. Tellingly, Gordon-Reed confesses to a twinge of gentle annoyance “when I initial listened to that others exterior of Texas claimed the getaway.”

I must admit I shared her original puzzlement, but for other reasons. Coming from a loved ones of transplanted Southerners, I didn’t expand up with any form of personalized relationship to this pink-letter working day. My moms and dads migrated to Los Angeles from Arkansas and Missouri, and their circle of mates hailed from spots like Louisiana, Mississippi and Puerto Rico, so Juneteenth celebrations ended up not a aspect of our summertime rituals. We didn’t rejoice Juneteenth in university in Compton, exactly where I grew up and exactly where the university year finished a several days before the 19th. I suspect the further reality is that back in those days it was rare to find a lot celebration of Blackness in my integrated Compton substantial university the South L.A. suburb was in the remaining throes of white flight that started out in the nineteen fifties when my moms and dads moved there from Watts.

Though there was undoubtedly acknowledgement of Black History 7 days — established in 1926 — at my A.M.E. church, calendars didn’t commemorate distinct dates in Black historical past. (Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday was celebrated only soon after his assassination in 1968 the initial Black History Month commemoration was arranged at Kent State some two years later on.) In our dwelling, historical past was shaped by a perception of struggle and triumph in excess of a dark tide of racial atrocities. Just one of the foundational tales my father explained to me associated getting all of a sudden uprooted, at sixteen, from his dwelling in Batesville, Ark., in 1925. A white kid experienced termed my father the N-term, which resulted in a struggle that the white kid did not win. A local Klansman, one particular of numerous who experienced their horses shod or their cars repaired at my grandfather’s blacksmith/auto restore enterprise, did him the courtesy of coming by that afternoon to tell him a lynching get together was coming for his only child.

While I’ve considering that acquired that lynchings ended up not as prevalent in Arkansas as in other states, my grandfather, born in 1887, would have listened to the horror tales of homicidal whites invading Blacks communities in East St. Louis, in Tulsa and, a lot nearer to dwelling, in Elaine, Ark. That was exactly where hundreds of Black individuals, according to estimates, ended up murdered in a 1919 massacre supposed to squelch a nascent sharecroppers’ union. (The horrors and financial devastation of Tulsa notwithstanding, some argue that Elaine stays amongst the deadliest massacre of Black individuals in U.S. historical past.)

Black detainees are rounded up by the Nationwide Guard in Tulsa, Okla., on June 1, 1921. By day’s end, numerous flourishing Black corporations in a 35-block spot experienced been torched and hundreds killed in what has appear to be regarded as the Tulsa Race Massacre.

(Tulsa Historical Modern society/AP)

My grandfather, I’m explained to, was grateful for the heads-up since it gave him a several precious hours to hurry dwelling, pack the family’s Product T with as numerous of their belongings as it would keep and escape with his wife and son. My grandfather was 38 years previous, younger by today’s criteria, but he’d previously outlived the life expectancy for a Black guy of his generation by five years. His need for a superior, for a longer period life for my father, Isaac, drove him to settle in Los Angeles, exactly where he established a similar enterprise in Watts that endured for some fifty years.

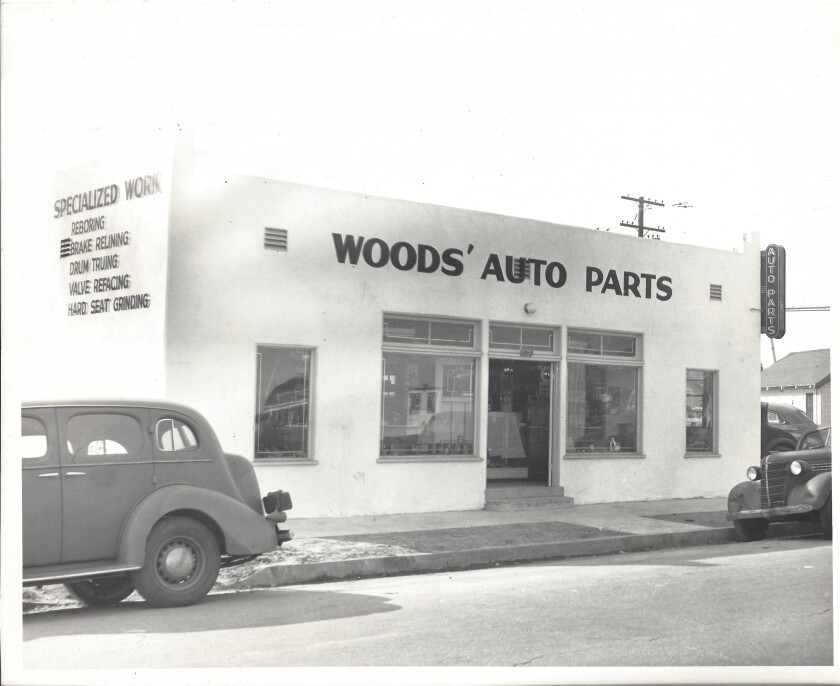

So, no, Juneteenth was not my most formative commemoration of Black historical past. It doesn’t even appear 2nd. That place belongs to Aug. eleven, 1965, the working day soon after my father’s birthday, when a website traffic cease of 21-year previous Marquette Frye escalated into law enforcement violence, sparking a conflagration that killed 34 individuals and wrecked some $forty million in home ($334 million in today’s pounds), typically in Black and Brown communities. (Woods’ Auto Components, at 108th Street and Compton Avenue, was spared.) I remember driving with my father to check on his enterprise some days soon after the violence started out and getting caught on a facet road concerning approaching Nationwide Guard armored cars and neighborhood residents, who’d utilised a auto to block the other end of the road, rifles and baseball bats at the ready.

Woods’ Auto Components circa nineteen forties.

(Isaac M. Woods)

The reframing, at past, of those so-termed riots as rebellions is the central premise of a intriguing new e-book by Elizabeth Hinton, “America on Fire.” A timeline at the end of Hinton’s e-book, listing hundreds of rebellions in Detroit, Harlem, Extensive Seashore and even Stockton, is an overwhelming chronicle of far more than five a long time of Black outrage, a lot of it driven by law enforcement violence. Obtaining my Watts in its webpages brings L.A.’s distressing historical past back to me in a way that is the two irritating and affirming — a sensation I envision Greenwood’s survivors and residents share as the horrors of the Tulsa massacre are commemorated in documentaries and a current presidential take a look at.

My initial genuine memory of Juneteenth was from a Black research class at USC. The injustice of Black individuals stored ignorant of their individual freedom for years appeared constant to me with the “divide and conquer” method I’d found deployed through historical past — for occasion in encouraging household slaves to experience exceptional to those in the fields, or in separating the targets of civil-rights integrationists from those of the radically transformative Black Panthers.

My personalized historical past, or yours, need to not obviate our collective duty to commemorate Juneteenth this year or to have an understanding of it as an crucial milestone in the winding down of institutional slavery. It grew to become one particular of in excess of 1,five hundred entries on Black historical past and achievement that Felix Liddell and I curated into an “African American Guide of Times,” printed just about 30 years in the past. Back then, I was driven to obtain little factors of mild in the dark historical past of racism — and to fill in the gaps in those “mainstream” guides of days that missed the Black existence in historical past, literature and the arts.

It was our excellent joy to incorporate pictures of African American wonderful artwork, to commemorate exhibits this kind of as LACMA’s landmark 1976 show “Two Hundreds of years of Black American Artwork,” to juxtapose that very long overdue announcement in Galveston with the moment, two years later on, when P.B.S. Pinchback — briefly the initial Black governor in the U.S. — urged Blacks to use their appropriate to vote. Or to discover one particular of the earliest Black criminal offense fiction writers, Rudolph Fisher, which eventually led me to edit a mystery anthology, create my individual mysteries and come to be a e-book critic. But distinct dates of Black exceptionalism need to not lull us into forgetting the darker commemorations or the fact that we as a nation even now have a great deal of get the job done to do to assure our collective freedom and protect our democracy.

For me, celebrating Juneteenth is about recognizing one particular small phase in reclaiming our full historical past. As Congress passes a monthly bill to make it a federal getaway, my only hope is that Juneteenth’s further concept of emancipation, its relationship to the ongoing quest for Black freedom and fairness, isn’t misplaced in the unavoidable onslaught of “Juneetenth Celebration and Sale” activities that undoubtedly await us.

What will I do this Juneteenth? With drink thoughts culled from the current L.A. Instances Food stuff Bowl dialogue of Black foodways for the getaway (the traditional pink soda h2o is not my issue), I approach to dig into Hinton’s e-book, reread Jessica B. Harris’ basic culinary historical past “High on the Hog” and savor the intriguing Stephen Satterfield Netflix series it inspired. I will crack open up Carol Anderson’s new e-book, “The Second,” about the astonishing racial historical past of the Second Modification. And need to the nonfiction get far too significant, I can revisit Jewell Parker Rhodes’ deeply impacting novel of the Tulsa Massacre, “Magic Town,” freshly reprinted with an author’s observe on the centenary of the tragedy.

Samantha Husbands of Los Angeles marches with the Juneteenth “Black Life Liberating the Black Community” Caravan/March along Martin Luther King Boulevard, ending at the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza on June 19, 2020.

(Gary Coronado/Los Angeles Instances)

Juneteenth, along with every single other sizeable date — joyful or otherwise, general public or personal — can help us reframe and refresh our country’s selective memory of American historical past. They are all crucial reminders that, as Emma Lazarus explained, “Until we are all free of charge, we are none of us free of charge.”

Woods is a e-book critic, editor and creator of several anthologies and criminal offense novels.

More Stories

Free Sheet Music – Earn Money Online by Composing Sheet Music Scores

8 Benefits of Listening to Music

Asian Artwork Through the Eyes of Janet Tava – Handbook Woodworkers and Weavers Gold Medallion Tapestry